I remember every single card and note I’ve ever received from my grandmother. The understated envelope. The heavy stationary. The beautiful cursive. And the time she took to sit down and spend the time to create that for me. It was special. And I’ve kept most of those. Why? Because they aren’t emails. They aren’t PostIt Notes or Hallmark Cards: they are individual expressions of interest and love.

I remember someone telling me that the most valuable thing that I had to give was my time. Not my money. Not my intelligence. Not my talents. My time. Because my time I could never get back. And wherever you give your time, that is where you heart it is. It shows your priorities. It shows that you care. Your time is your most valuable possession.

When you sit down and write a Thank-You Note, aside from whatever you put down on paper, you are telling that person, “You matter to me.” And that is something we don’t tell people nearly often enough these days.

This fantastic article was originally published in The New York Times, written by Guy Trebay. We hope you enjoy it.

-Fascinately

The Found Art of Thank-You Notes

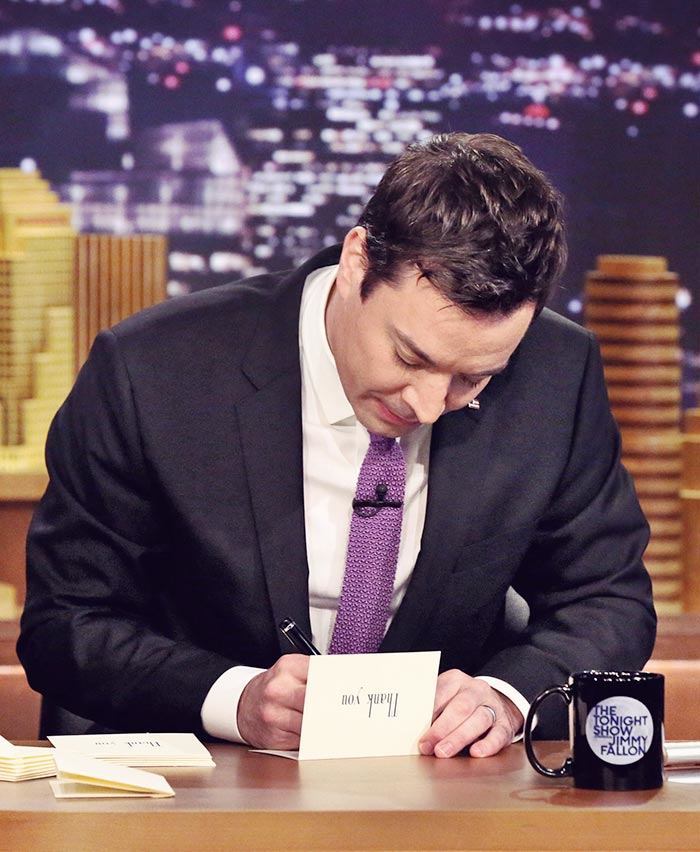

When Jimmy Fallon sits down to write his weekly thank-you notes on “The Tonight Show,” he is both ribbing and breathing life into a custom many felt was headed the way of the dodo. “Thank you, cotton candy,” Mr. Fallon scribbles on a correspondence card, “for making my grandmother’s hair look delicious.” Thank you, “bowling, for giving me an excuse to drink with somebody else’s shoes on.”

“Thank you, Chris Christie,” he writes, “for going back for seconds.”

Mr. Fallon’s routine is a hoot, of course, a joke that points up the truth that the boring stuff your parents made you do never actually goes out of fashion and that also inadvertently supports recent scientific findings linking gratitude to increased optimism, stress reduction and a better night’s sleep. Few who sit down to write a bread-and-butter note are likely to be aware that by doing so they are not only on trend but also on their way to becoming happier and more sociable people. Apparently, what Emily Post termed good manners (science prefers “gratitude intervention”) has all kinds of unexpected benefits. And as it happens, the handwritten gratitude intervention seems to be experiencing a moment of vogue.

The personal and professional thank-you notes Cristiano Magni, a New York fashion publicist, sends routinely are written on weighty ecru Connor correspondence cards adorned with a rhinoceros embossed in gold. “It is so important, in a digital world, to have the dignity to sit down and write something in your own hand,” Mr. Magni said one recent afternoon in a garment district showroom, where a collection of thank-you notes sent by editors and stylists was spread across his desk.

Fashion was a business notoriously late to adapt to digital technology, and it remains one in which such seemingly anachronistic customs as the handwritten note hang on stubbornly. Anna Wintour is a stickler for them. So, to judge by Mr. Magni’s collection, are editors at Lucky, Vanity Fair, Esquire and Harper’s Bazaar.

“It not only strengthens the bonds between people, in your personal life and in business,” he said of the custom, “it also rings an emotional chord.”

While researchers leave open the matter of which format is best for rendering thanks for small favors, courtesies, presents or a tuna casserole supper, there is a growing sense that the old, reliable handwritten note is making a comeback — and not just as a prop on “Tonight.”

For Martin Nowak, director of Harvard’s Program for Evolutionary Dynamics, thanking is a form of cooperative reciprocity with roots in primate behavior. For Paula Madden, a real estate developer in Portland, Ore., “Good manners are the basis of civilization.”

This truth is not, alas, universally acknowledged, added Ms. Madden, who manages a portfolio of family-owned properties and also oversees Portland’s Friday Evening Dancing Class for children, a social institution now in its 92nd year. “As you grow older, it becomes more important when someone recognizes the effort you have made on their behalf and reciprocates in the form of a written acknowledgment,” she said.

A text message just doesn’t cut it, Ms. Madden said, for the simple reason that conveying emotion in digital formats is a lost cause. Somehow thickets of exclamation points, ALL CAPS shouts, loaded acronyms and chirpy emoticons cannot approach the freight of feeling conveyed on a scrap of paper with words scratched on it by hand. Why?

“There are a lot of elements,” William Miller, proprietor of the Printery in Oyster Bay, N.Y., said recently. For decades, the Printery has supplied custom writing paper to North Shore swells along with clients as discriminating as Ralph Lauren and Graydon Carter, the editor of Vanity Fair. “Engraved stationery has a sculptural quality, shadow lines, artful arrangement of colors,” Mr. Miller said. Despite the incursions of electronic media, he added, “the handwritten note is very much alive and well.”

Mr. Carter writes his on correspondence cards whose weight and texture are selected for how ink flows across them from the fountain pens he prefers. “Graydon is really particular,” Mr. Miller said. “As with Graydon, a lot of people use a correspondence card to say thank you in business, but in a way that has a social affectation. They want to re-emphasize the personal relationship.”

What they want, said Liz Quinn, the owner of Stationer on Sunrise in Palm Beach, Fla., is to draw a distinction between the tossed-off, compressed nature of electronic messages and a form of ritualized communication that gives material evidence “that the person really did appreciate something.”

Text and email “don’t mean anything anymore,” Ms. Quinn said, adding with a laugh that her own smartphone, of course, accounted for 90 percent of her correspondence. Make that 100 percent in the case of most millennials and aughties.

“It’s definitely important to show your gratitude, because not everything is going to be given to you,” Brooke Egerton-Warburton, a seventh grader on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, said recently. “But gratitude comes in different forms.”

At that, Ms. Egerton-Warburton’s twin sister chimed in with a litany of alternatives. “It’s, like, ‘This is my phone, this is my email, this is my Instagram, this is my Twitter,’ ” Avery Egerton-Warburton said. “If you want to say thank you, just send me a text.”

In 1960s Baltimore, when Catherine Kitz was growing up, stationery was an essential part of a social wardrobe. “Growing up in a black family, that was something we were raised to do, to send a thank-you note,” Ms. Kitz, a museum administrator in Oakland, Calif., said. “I saw people of all economic backgrounds and races sending them, and now I see people of all economic and racial backgrounds not sending them.”

Despite her best efforts to instill in her stepgrandchildren the importance of forging bonds of trust and dependence through ritualized thanksgiving, the handwritten thank-you note, Ms. Kitz noted, may be a generational lost cause. “After a while I stopped trying,” she said. “I’m still I’m hoping they’ll figure it out at some point — in school, in college, when they get their first job.”

In all likelihood, they will. “Ink on paper has been challenged on many fronts,” said Patti Stracher, director of the National Stationery Show, expected to draw 800 exhibitors and 12,000 attendees to the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in May. “Thank-you notes, however, are one of the areas that a poor economy or a social culture shift has little impact on.”

Heather Wiese, owner of Bell’Invito, a luxury stationer in Dallas, said, “If you want to stand out, to be more polished, probably the easiest thing you can do is write that thank-you note.” She added: “Social media, texting and email are all completely relevant. But if after I’ve put my effort forward to interview a potential employee what I get is an email that looks exactly like 200 others, I may miss it.”

Where messages in an inbox look little different from spam, a tidy square in a mailbox crammed with bills commands attention. So does the vision of that other anachronism: penmanship.

“If you are entertained by anyone in their home, that is such an honor it should be followed up by a note of thanks,” said Kathryn Urban, a community volunteer in San Francisco. “Sometimes there are kind acts people have done. Sometimes in a note you can express something difficult to say in person,” or else in an email or text. And sometimes you want to share the tactile, visual and olfactory pleasure provided by a thank-you card, whether a blind embossed engraved one or a Hallmark card bought at CVS.

One of the first things Carroll Irene Gelderman, a Columbia University student from New Orleans, did when she was named the 2014 Queen of Carnival was to order new stationery. As custom dictates, Mardi Gras queens are typically showered with tribute by their courts, and Ms. Gelderman was no different. Before Fat Tuesday rolled round, she had already received over 600 individual gifts.

The pearl white cards Ms. Gelderman chose for her thank-you notes are engraved in dove gray ink by Arzberger and bear her name engraved in Roman lettering at the top. The envelopes were lined with gray-and-white patterned paper, and a custom shade of ink slightly darker than the paper was ordered from Iroshizuku to fill her fountain pen.

“Like a lot of people in my generation, I might think, ‘Oh, just send them a text,’ ” said Ms. Gelderman, who is 20. “But I actually enjoyed writing the notes because in the process of opening a note, feeling the paper, seeing the imperfection of the writing, reading the message in another person’s voice, you actually feel like you have a piece of that person in your hand.”